Inner Circle is your update on what’s happening at and adjacent to Open Research Institute. We’re a non-profit dedicated to open source digital radio work. We support technical and regulatory efforts. A major beneficiary of this work is the amateur radio services. Sign up at this link http://eepurl.com/h_hYzL

Amaranth in

practice: a case study with Maia SDR

Maia SDR is a new open-source FPGA-based SDR project focusing on the

ADALM Pluto. The longer term goals of the project are to foster

open-source development of SDR applications on FPGA and to promote the

collaboration between the open-source SDR and FPGA communities. For the

time being, focusing on developing a firmware image for the ADALM Pluto

that uses the FPGA for most of the signal processing provides realistic

goals and a product based on readily available hardware that people can

already try and use during early stages of development.

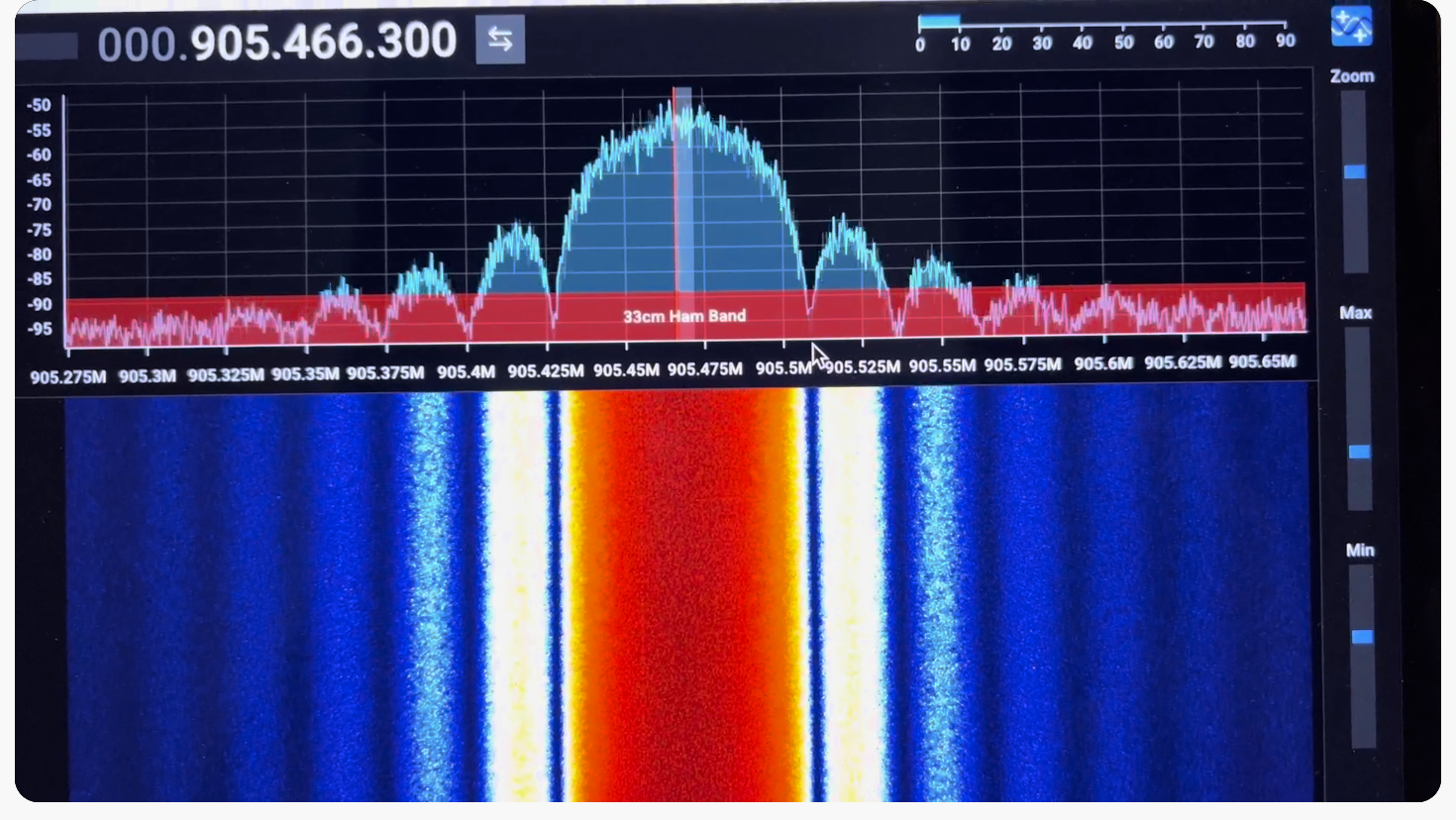

The first version of Maia SDR was released on Februrary 2023, though

its development started in September 2022. This version has a

WebSDR-like web interface that displays a realtime waterfall with a

sample rate of up to 61.44Msps and is able to make IQ recordings at that

rate to the Pluto DDR (up to a maximum size of 400MiB per recording).

These recordings can then be downloaded in SigMF format.

Exploring the RF world in the field with a portable device is one of

the goals of Maia SDR, so its web UI is developed having in mind the

usage from a smartphone and fully supports touch gestures to zoom and

scroll the waterfall. A Pluto connected by USB Ethernet to a smartphone

already give a quite capable and portable tool to discover and record

signals.

The following figure shows a screenshot of the Maia SDR web user

interface. More information about the project can be found in

https://maia-sdr.net

Amaranth

Amaranth

Amaranth is an open-source HDL based in Python. The project is led by

Catherine “whitequark”, who is one of the most active and prolific

developers in the open-source FPGA community. Amaranth was previously

called nMigen, as it was initially developed as an evolution of the

Migen FHDL by M-Labs.

I cannot introduce Amaranth any better than Catherine, so I will just

cite her words from the README and documentation.

The Amaranth project provides an open-source toolchain for developing

hardware based on synchronous digital logic using the Python programming

language, as well as evaluation board definitions, a System on Chip

toolkit, and more. It aims to be easy to learn and use, reduce or

eliminate common coding mistakes, and simplify the design of complex

hardware with reusable components.

The Amaranth toolchain consists of the Amaranth hardware definition

language, the standard library, the simulator, and the build system,

covering all steps of a typical FPGA development workflow. At the same

time, it does not restrict the designer’s choice of tools: existing

industry-standard (System)Verilog or VHDL code can be integrated into an

Amaranth-based design flow, or, conversely, Amaranth code can be

integrated into an existing Verilog-based design flow.

The Amaranth

documentation gives a tutorial for the language and includes as a

first example the following counter with a fixed limit.

from amaranth import *

class UpCounter(Elaboratable):

"""

A 16-bit up counter with a fixed limit.

Parameters

----------

limit : int

The value at which the counter overflows.

Attributes

----------

en : Signal, in

The counter is incremented if ``en`` is asserted, and retains

its value otherwise.

ovf : Signal, out

``ovf`` is asserted when the counter reaches its limit.

"""

def __init__(self, limit):

self.limit = limit

# Ports

self.en = Signal()

self.ovf = Signal()

# State

self.count = Signal(16)

def elaborate(self, platform):

m = Module()

m.d.comb += self.ovf.eq(self.count == self.limit)

with m.If(self.en):

with m.If(self.ovf):

m.d.sync += self.count.eq(0)

with m.Else():

m.d.sync += self.count.eq(self.count + 1)

return m

Amaranth Elaboratable‘s are akin to Verilog

module‘s (and in fact get synthesized to

module‘s if we convert Amaranth to Verilog). IO ports for

the module are created in the __init__() method. The

elaborate() method can create additional logic elements

besides those created in __init__() by instantiating more

Signal‘s (this example does not do this). It also describes

the logical relationships between all these Signals by

means of a Module() instance usually called m.

Essentially, at some point in time, the value of a Signal

changes depending on the values of some Signal‘s and

potentially on some conditions. Such point in time can be either

continuously, which is described by the m.d.comb

combinational domain, or at the next rising clock edge, which

is described by the m.d.sync synchronous domain (which is,

roughly speaking, the “default” or “main” clock domain of the module),

or by another clock domain. Conditions are expressed using

with statements, such as with m.If(self.en),

in a way that feels quite similar to writing Python code.

For me, one of the fundamental concepts of Amaranth is the division

between what gets run by Python at synthesis time, and what gets run by

the hardware when our design eventually comes to life in an FPGA. In the

elaborate() method we have a combination of “regular”

Python code, which will get run in our machine when we convert the

Amaranth design to Verilog or generate a bitstream directly from it, as

well as code that describes what the hardware does. The latter is also

Python code, but we should think that the effects of running it are only

injecting that description into the list of things that Amaranth knows

about our hardware design.

Code describing the hardware appears mainly in two cases: First, when

we operate with the values of signals. For instance,

self.count + 1 does not take the value of

self.count and add one to it when the Python code is run.

It merely describes that the hardware should somehow obtain the sum of

the value of the register corresponding to self.count and

the constant one. This expression is in effect describing a hardware

adder, and it will cause an adder to appear in our FPGA design. This

behaviour is reminiscent of how Dask and other packages based on lazy

evaluation work (in Dask, operations with dataframes only describe

computations; the actual work is only done eventually, when the

compute() method is called). I want to stress that the

expression self.count + 1 might as well appear in

elaborate() only after a series of fairly complicated

if and else statements using regular Python

code. These statements will be evaluated at synthesis time, and our

hardware design will end up having an adder or not depending on these

conditions. Similarly, instead of the constant 1 in the

+ 1 operation, we could have a Python variable that is

evaluated in synthesis time, perhaps as the result of running fairly

complicated code. This will also affect what constant the hardware adder

that we have in our design adds to the value of the

self.count register.

Secondly, we have the control structures: m.If,

m.Else, and a few more. These also describe hardware.

Whether the condition is satisfied is not evaluated when the Python

script runs. What these conditionals do is to modify the hardware

description formed by the assignments to m.d.sync and

m.d.comb that they enclose so that these assignments are

only effective (or active) in the moments in which the condition is

satisfied. In practice, these statements do two things in the resulting

hardware: They multiplex between several intermediate results depending

on some conditions, in a way that is usually more readable than using

the Mux() operator that Amaranth also provides. They also

control what logic function gets wired to the clock enable of

flip-flops. Indeed, in some conditions a synchronous

Signal() may have no active statements, in which case it

should hold its current value. This behaviour can be implemented in

hardware either by deasserting the clock enable of the flip-flops or by

feeding back the output of the flip-flops to their input through a

multiplexer. What is done depends mainly on choices done by the

synthesis tool when mapping the RTL to FPGA elements. As before, we can

have “regular” Python code that is run at synthesis time modifying how

these m.If control structures look like, or even whether

they appear in the design at all.

In a sense, the regular Python code that gets run at synthesis time

is similar to Verilog and VHDL generate blocks. However,

this is extremely more powerful, because we have all the expressiveness

and power of Python at our disposal to influence how we build our design

at synthesis time. Hopefully the following examples from Maia SDR can

illustrate how useful this can be.

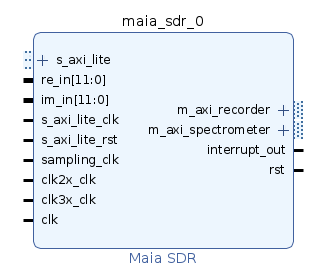

maia-hdl

maia-hdl is the FPGA design of Maia SDR. It is bundled as a Python

package, with the intention to make easy to reuse the modules in third

party designs. The top level of the design is an Amaranth

Elaboratable that gets synthesized to Verilog and packaged

as a Vivado IP core. As shown below, the IP core has re_in

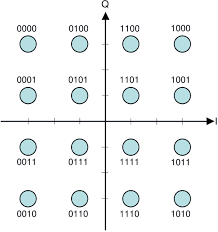

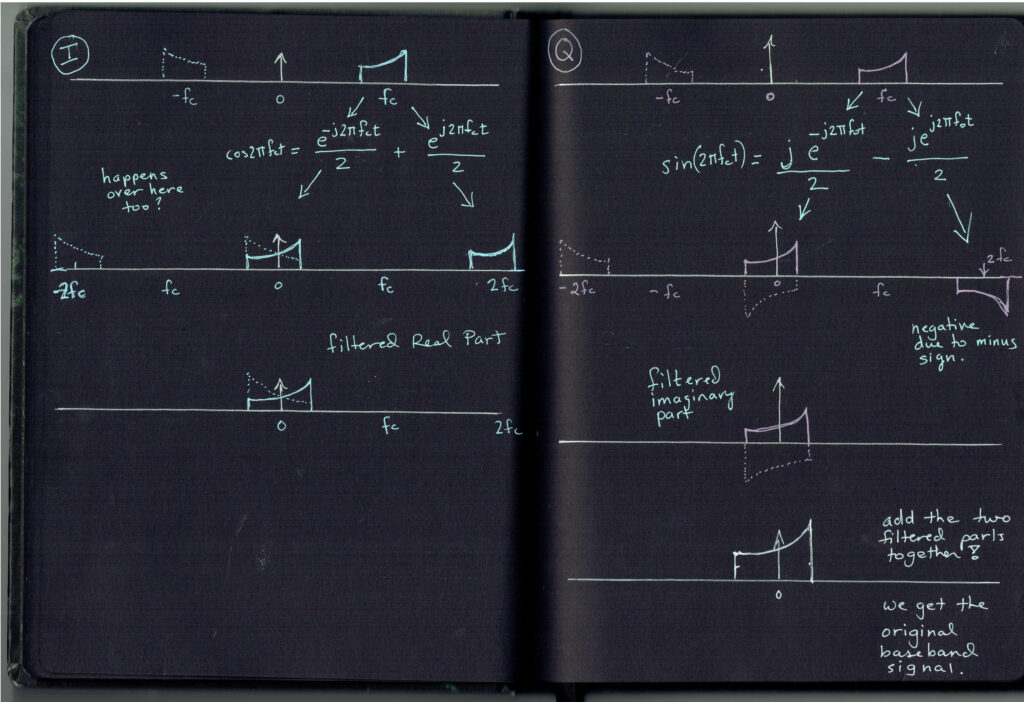

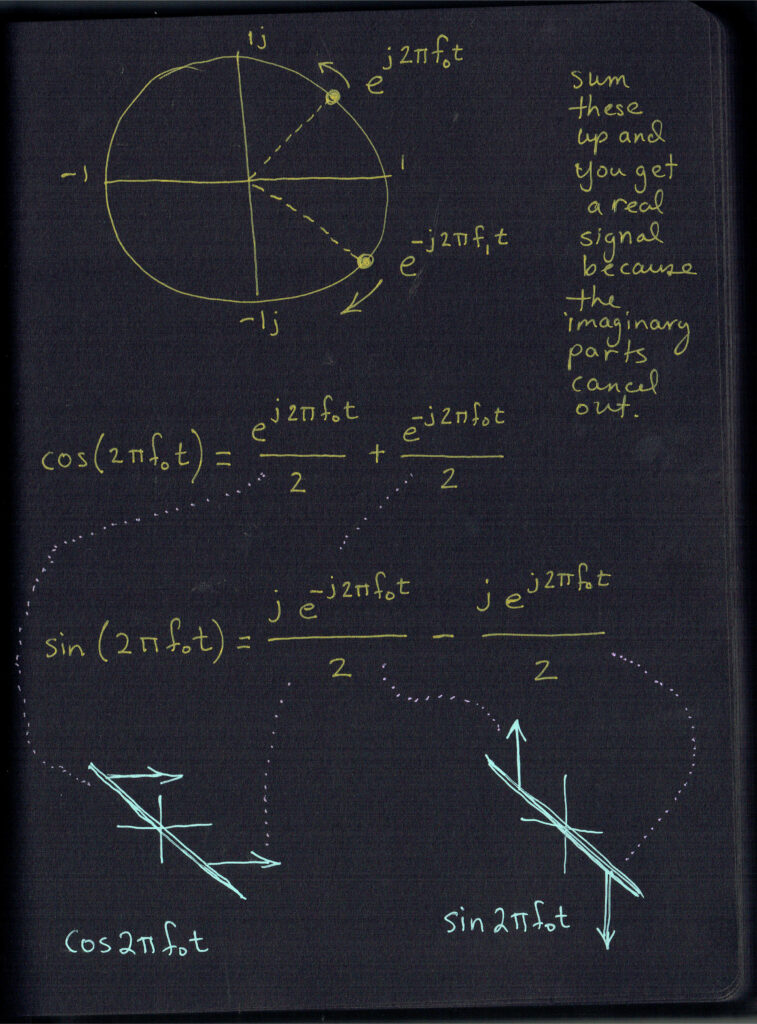

and im_in ports for the IQ data of the ADC, an AXI4-Lite

subordinate interface to allow the ARM processor to control the core

through memory-mapped registers, AXI3 manager interfaces for the DMAs of

the spectrometer (waterfall) and IQ recorder, and ports for clocking and

reset.

The IP core is instantiated in the block design of a Vivado project

that gets created and implemented using a TCL script. This is based on

the build system used by Analog Devices for the default Pluto FPGA

bitstream. In this respect, Maia SDR gives a good example of how

Amaranth can be integrated in a typical flow using the Xilinx tools.

There are two classes of unit tests in maia-hdl. The first are

Amaranth simulations. These use the Amaranth simulator, which is a

Python simulator than can only simulate Amaranth designs. These tests

give a simple but efficient and powerful way of testing Amaranth-only

modules. The second are cocotb simulations. Cocotb is an open-source

cosimulation testbench environment for verifying VHDL and Verilog

designs using Python. Briefly speaking, it drives an HDL simulator using

Python to control the inputs and check the outputs of the device under

test. Cocotb has rich environment that includes Python classes that

implement AXI devices. In maia-hdl, cocotb is used together with Icarus

Verilog for the simulation of designs that involve Verilog modules

(which happens in the cases in which we are instantiating from Amaranth

a Xilinx primitive that is simulated with the Unisim library), and for

those simulations in which the cocotb library is specially useful (such

as for example, when using the cocotb AXI4-Lite Manager class to test

our AXI4-Lite registers).

One of the driving features of Maia SDR is to optimize the FPGA

resource utilization. This is important, because the Pluto Zynq-7010

FPGA is not so large, specially compared with other Xilinx FPGAs. To

this end, Amaranth gives a good control about how the FPGA design will

look like in terms of LUTs, registers, etc. The example with the counter

has perhaps already shown that Amaranth is a low-level language, in the

same sense that Verilog and VHDL are, and nothing comparable to HLS

(where regular C code is translated to an FPGA design).

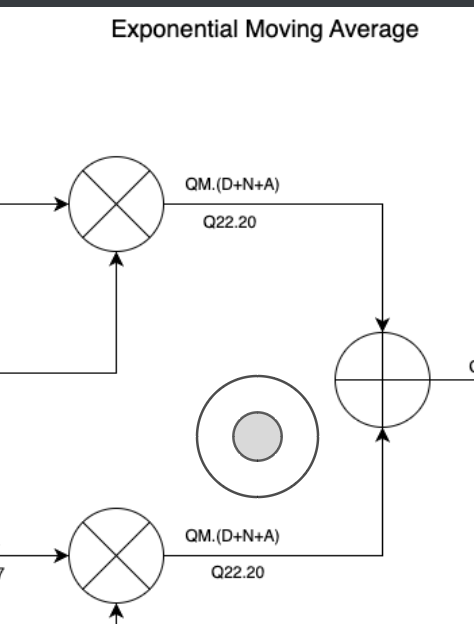

FFT

The main protagonist of the Maia SDR FPGA design is a custom

pipelined FFT core that focuses on low resource utilization. In the Maia

SDR Pluto firmware it is used as a radix-2² single-delay-feedback

decimation-in-frequency 4096-point FFT with a Blackman-harris window. It

can run at up to 62.5 Msps and uses only around 2.2 kLUTs, 1.4

kregisters, 9.5 BRAMs, and 6 DSPs. One of the tricks that allows to save

a lot of DSPs is to use a single DSP for each complex multiplication, by

performing the three required real products sequentially with a 187.5

MHz clock. A description of the design of the FFT core is out of the

scope of this article, but I want to show a few features that showcase

the strengths of Amaranth.

The first is the FFTControl module. The job of this

module is to generate the control signals for all the elements of the

FFT pipeline. In each clock cycle, it selects which operation each

butterfly should do, which twiddle factor should be used by each

multiplier, as well as the read and write addresses to use for the delay

lines that are implemented with BRAMs (these are used for the first

stages of the pipeline, which require large delay lines). As one can

imagine, these control outputs are greatly dependent on the

synchronization of all the elements. For example, if we introduce an

extra delay of one cycle in one of the elements, perhaps because we

register the data to satisfy timing constraints, all the elements

following this in the pipeline will need their control inputs to be

offset in time by one cycle.

It is really difficult to implement something like this in Verilog or

VHDL. Changing these aspects of the synchronization of the design

usually requires rethinking and rewriting parts of the control logic. In

Amaranth, our modules are Python classes. We can have them “talk to each

other” at synthesis time and agree on how the control should be set up,

in such a way that the result will still work if we change the

synchronization parameters.

For example, all the classes that are FFT pipeline elements implement

a delay Python @property that states what is

the input to output delay of the module measured in clock cycles. For

some simple modules this is always the same constant, but for a

single-delay-feedback butterfly it depends on the length of the delay

line of the butterfly, and for a twiddle factor multiplier it depends on

whether the multiplier is implemented with one or three DSPs. These are

choices that are done at synthesis time based on parameters that are

passed to the __init__() method of these modules.

The FFTControl module can ask at synthesis time to all

the elements that form the FFT pipeline what are their delays, and

figure out the reset values of some counters and the lengths of some

delay lines accordingly. This makes the control logic work correctly,

regardless what these delays are. For instance, the following method of

FFTControl computes the delay between the input of the FFT

and the input of each butterfly by summing up the delays of all the

preceding elements.

def delay_butterflies_input(self):

"""Gives the delay from the FFT input to the input of each of the

butterflies"""

return [

self.delay_window

+ sum([butterfly.delay for butterfly in self.butterflies[:j]])

+ sum([twiddle.delay for twiddle in self.twiddles[:j]])

for j in range(self.stages)

]

This is then used in the calculation of the length of some delay

lines that supply the control signals to the butterflies. The code is

slightly convoluted, but accounts for all possible cases. I don’t think

it would be reasonable to do this kind of thing in Verilog or VHDL.

mux_bfly_delay = [

[Signal(2 if isinstance(self.butterflies[j], R22SDF) else 1,

name=f'mux_bfly{j}_delay{k}', reset_less=True)

for k in range(0,

delay_butterflies_input[j]

- delay_twiddles_input[j-1]

+ self.twiddles[j-1].twiddle_index_advance)]

for j in range(1, self.stages)]

Another important aspect facilitated by Amaranth is the construction

of a model. We need a bit-exact model of our FFT core in order to be

able to test it in different situations and to validate simulations of

the Amaranth design against the model. Each of the modules that form the

pipeline has a model() method that uses NumPy to calculate

the output of that module given some inputs expressed as NumPy arrays.

Here is the model for a radix-2 decimation-in-frequency

single-delay-feedback butterfly. Perhaps it looks somewhat reasonable if

we remember that such a butterfly basically computes first

x[n] + x[n+v//2], for n = 0, 1, ..., v//2-1,

and then x[n] - x[n+v//2] for

n = 0, 1, ..., v//2-1.

[class R2SDF(Elaboratable):]

[...]

def model(self, re_in, im_in):

v = self.model_vlen

re_in, im_in = (np.array(x, 'int').reshape(-1, 2, v // 2)

for x in [re_in, im_in])

re_out, im_out = [

clamp_nbits(

np.concatenate(

(x[:, 0] + x[:, 1], x[:, 0] - x[:, 1]),

axis=-1).ravel() >> self.trunc,

self.w_out)

for x in [re_in, im_in]]

return re_out, im_out

The interesting thing is that, since each of the FFT pipeline modules

has its individual model, it is easy to verify the simulation of each

module against its model separately. The model of the FFT

module, which represents the whole FFT core, simply puts everything

together by calling the model() methods of each of the

elements in the pipeline in sequence. An important detail here is that

the arrays self._butterflies and

self._twiddles are the same ones that are used to

instantiate and connect together the pipeline modules, in terms of the

hardware design. By having these synergies between the model and the

hardware design, we reduce the chances of them getting out of sync due

to code changes.

[class FFT(Elaboratable):]

[...]

def model(self, re_in, im_in):

v = self.model_vlen

re = re_in

im = im_in

if self._window is not None:

re, im = self._window.model(re, im)

for j in range(self.nstages):

re, im = self._butterflies[j].model(re, im)

if j != self.nstages - 1:

re, im = self._twiddles[j].model(re, im)

return re, im

Instantiating

Verilog modules and primitives

A question that often comes up is how to instantiate Verilog modules,

VHDL entities or FPGA primitives in an Amaranth design. Kate Temkin has

a short blog

post about it. In maia-hdl this is used in in several cases, such as

to implement clock domain crossing with the Xilinx FIFO18E1 primitive.

The most interesting example is however the Cmult3x module,

which implements complex multiplication with a single DSP48E1 that runs

at three clock cycles per input sample (some simple algebra shows that a

complex multiplication can be written with only three real

multiplications).

When designing modules with DSPs, I prefer to write HDL code that

will make Vivado infer the DSPs I want. This is possible in simple

cases, but in more complicated situations it is not possible to make

Vivado understand exactly what we want, so we need to instantiate the

DSP48 primitives by hand.

The drawback of having an Amaranth design that contains instances of

Verilog modules, VHDL entities or primitives is that we can no longer

simulate our design with the Amaranth simulator. If our instances have a

Verilog model (such as is the case with Xilinx primitives via the Unisim

library), we can still convert the Amaranth design to Verilog and use a

Verilog simulator. This is done in maia-hdl using Icarus Verilog and

cocotb. However, this can be somewhat inconvenient.

There is another possibility, which is to write different

implementations of the same Amaranth module. One of them can be pure

Amaranth code, which we will use for simulation, and another can use

Verilog modules or primitives. The two implementations need to be

functionally equivalent, but we can check this through testing.

The way to acomplish this is through Amaranth’s concept of platform.

The platform is a Python object that gets passed to the

elaborate() methods of the modules in the design. The

elaborate methods can then ask the platform for some objects that are

usually dependent on the FPGA family, such as flip-flop synchronizers.

This is a way of building designs that are more portable to different

families. The platform objects are also instrumental in the process of

building the bitstream completely within Amaranth, which is possible for

some FPGA families that have an open-source toolchain.

In the case of the maia-hdl Cmult3x we simply check

whether the platform we’ve been passed is an instance of

XilinxPlatform and depending on this we have the

elaborate() method either describe a pure Amaranth design

that models the DSP48 functionality that we need, or instantiate a

DSP48E1 primitive. Note that in the case of the pure Amaranth design we

do not model the full functionality of the DSP48. Only that which is

applicable to this use case.

[class Cmult3x(Elaboratable):]

[...]

def elaborate(self, platform):

if isinstance(platform, XilinxPlatform):

return self.elaborate_xilinx(platform)

# Amaranth design. Vivado doesn't infer a single DSP48E1 as we want.

[ ... here a pure amaranth design follows ... ]

def elaborate_xilinx(self, platform):

# Design with an instantiated DSP48E1

[...]

m.submodules.dsp = dsp = Instance(

'DSP48E1',

[...]

Registers

Another aspect where the flexibility of Amaranth shines is in the

creation of register banks. In maia-hdl, the module

Register corresponds to a single 32-bit wide register and

the module Registers forms a register bank by putting

together several of these registers, each with their corresponding

address. The registers support a simple bus for reads and writes, and an

Axi4LiteRegisterBridge module is provided to translate

between AXI4-Lite and this bus, allowing the ARM CPU to access the

registers.

Registers and register banks are created with Python code that

describes the fields of the registers. The basic ingredient is the

Field named tuple:

Field = collections.namedtuple('RegisterField',

['name', 'access', 'width', 'reset'])

We describe a register by giving it a name, an access mode (which can

be read-only, write-only, read-write, or some other more specialized

modes that we will describe below), a width, and a reset or default

value.

The best way to understand how to work with these registers is to see

how they are used in the Maia SDR top-level design.

self.control_registers = Registers(

'control',

{

0b00: Register(

'product_id', [

Field('product_id', Access.R, 32, 0x6169616d)

]),

0b01: Register('version', [

Field('bugfix', Access.R, 8,

int(_version.split('.')[2])),

Field('minor', Access.R, 8,

int(_version.split('.')[1])),

Field('major', Access.R, 8,

int(_version.split('.')[0])),

Field('platform', Access.R, 8, 0),

]),

0b10: Register('control', [

Field('sdr_reset', Access.RW, 1, 1),

]),

0b11: Register('interrupts', [

Field('spectrometer', Access.Rsticky, 1, 0),

Field('recorder', Access.Rsticky, 1, 0),

], interrupt=True),

},

2)

self.recorder_registers = Registers(

'recorder',

{

0b0: Register('recorder_control', [

Field('start', Access.Wpulse, 1, 0),

Field('stop', Access.Wpulse, 1, 0),

Field('mode_8bit', Access.RW, 1, 0),

Field('dropped_samples', Access.R, 1, 0),

]),

0b1: Register('recorder_next_address', [

Field('next_address', Access.R, 32, 0),

]),

},

1)

Here we show two register banks: one for the control of the IP core

and another for the control of the IQ recorder. There is a similar third

register bank for the control of the spectrometer (waterfall).

The parameters of the Registers constructor are a name,

a dictionary that contains the registers in the bank (the keys of the

dictionary are the addresses, and the values are the

Register objects), and the width of the address bus. Note

that these addresses correspond to the addressing of the native register

bus. When we convert to AXI4-Lite, the addresses get shifted by two bits

to the left because each register is 4 bytes wide.

The parameters of the Register constructor are a name

and a list of Field‘s describing the fields of the

register. Fields are allocated into the 32-bit register according to

their order in the list, starting by the LSB. For instance, in the

interrupts register, the spectrometer field

occupies the LSB and the recorder field occupies the next

bit.

If we look at the control registers, we can see that the

registers for product_id and version have

access type R, which means read-only. These registers are

never wired in the design to other signals that would override their

default values, so they are in fact constants that the CPU can read to

check that the IP core is present and find its version number.

Next we have a control register, which has an

sdr_reset field. This is wired internally to a bunch of

reset signals in the IP core. It has a default value of 1, which means

that most of the IP core starts in reset. The CPU can write a 0 to this

field to take the IP core out of reset before using it. Accessing this

sdr_reset field within the design is very simple, because

the Registers and Register implement

__getitem__(), allowing us to access them as if they were

dictionaries. This example shows how it works. Here we are connecting

the field sdr_reset to the reset input of something called

rxiq_cdc (which implements clock domain crossing between

the ADC sampling clock and the internal clock used in the IP core).

m.d.comb += rxiq_cdc.reset.eq(

self.control_registers['control']['sdr_reset'])

If we look at the interrupts register, we can see an

example of the Rsticky access mode. This means read-only

sticky. A field of this type will be set to 1 when its input (which is

wired internally in the IP core) has the value 1. It will keep the value

1 even if the input goes back to 0. The field is cleared and set to 0

when it is read. The intended use for this access mode is interrupts. A

module can pulse the input of the field to notify an interrupt, and the

field will hold a 1 until the CPU reads the register, clearing the

interrupts. The interrupts register even has an

interrupt=True option that provides an interrupt output

that can be connected directly to the F2P interrupt port of the Zynq.

This interrupt output will be high whenever any Rsticky

field in the register is non-zero.

Finally, the recorder_control field gives some examples

of the Wpulse access type. This is a write-only field with

pulsed output. Writing a 1 to this field causes a one-cycle pulse at its

output. This is ideal for controlling modules that require a pulse to

indicate some event or command. For example, this is the case with the

start and stop commands of the IQ recorder.

The Amaranth code that makes all of this work is not so complicated.

You can take a look at the register.py file in maia-hdl to

see for yourself.

Another interesting feature of this register system is that it can

write an SVD file describing the register map. CMSIS-SVD is an XML

format that is often used to describe the register maps of

microcontrollers and SoCs. Maia SDR uses svd2rust to

generate a nice Rust API for register access.

The Registers and Register classes have

svd() methods that generate the SVD XML using Python’s

xml.etree.ElementTree. This is relatively simple, because

the classes already have all the information about these registers. It

is, after all, the same information that they use to describe the

hardware implementation of the registers. This is another example of how

by using synergies between the code that describes the hardware design

and code that does something related to that hardware design (in this

case, writing SVD), we make it harder for changes in the code base to

cause inconsistencies.

Conclusions

In this article we have gone from a “hello world” type counter in

Amaranth to some rather intricate code from the inner workings of an FFT

core. My intention with giving these code examples is not to expect the

reader to understand all the code, but rather to give a feeling for how

using Amaranth in complex projects can look like. Perhaps by now I have

managed to convince you that Amaranth is a powerful and flexible

alternative to HDLs such as Verilog and VHDL, or at least to get you

interested in learning more about Amaranth and the world of open-source

FPGA and silicon design.

Want someone on your side at the FCC? We have good news. The FCC TAC is going to resume work. The previous term ended in December 2022 with an in-person meeting in Washington, DC. ORI was a member of the AI/ML Working Group and served as a co-chair of the “Safe Uses of AI/ML” sub-working group. The next term will be for two years. The appointment will require another round of nominations and vetting. An invitation to ORI has been made. ORI will speak up for open source digital radio work and the amateur radio services. Thank you to everyone that made the 2022 FCC TAC term productive and beneficial. Join the #ai channel on ORI Slack to get more involved. Not part of Slack? Visit https://openresearch.institute/getting-started to Get Started.

Sign-ups are live at https://us.commitchange.com/ca/san-diego/open-research-institute/campaigns/hdl-coder-for-software-defined-radio

Advanced training for Digital Communications, Software Defined Radio, and FPGAs will be held 1-5 May 2023. Do you know someone that can benefit from customized and focused training? Please forward this email to them. Designed to benefit open source digital radio, this course also benefits the amateur radio services.

Presented by ORI and taught by Mathworks, this class will cover the following topics.

Prepare a Simulink model for HDL code generation. Generate HDL code and testbench for simple models requiring no optimization.

Establish correspondence between generated HDL code and specific Simulink blocks in the model. Use Fixed-Point Tool to finalize fixed point architecture of the model.

Use pipelines to meet design timing requirements. Use specific hardware implementations and share resources for area optimization.

Signal Flow Graph (SFG) Techniques (SFG) Techniques and high-speed FIR design (2.0 hrs)

Review the representation of DSP algorithms using signal flow graph. Use the Cut Set method to improve timing performance. Implement parallel and serial FIR filters.

Develop polyphase structure for efficient implementation of multirate filters. Use CIC filter for interpolation and decimation.

Introduce CORDIC algorithm for calculation of various trigonometric functions.

Day 3 – Programming Xilinx Zynq SoCs with MATLAB and Simulink & Software-Defined Radio with Zynq using Simulink

Use HDL Workflow Advisor to configure a Simulink model, generate and build both HDL and C code, and deploy to Zynq platform.

Model and simulate RF signal chain and communications algorithms.

Verify the operation of baseband transceiver algorithm using real data streamed from the AD9361 into MATLAB and Simulink.

Generate HDL and C code targeting the programmable logic (PL) and processing system (PS) on the Zynq SoC to implement TX/RX.

Want to learn more about open source FPGA development from experts in the field? Ready to capitalize on the HDL Coder for Software Defined Radio Class happening in May 2023? Want to get away? How about something that can give you both? We are looking at organizing an FPGA Workshop Adventure Cruise. Be part of the planning and write fpga@openresearch.institute

Consider being part of the board. We’d like to expand from 5 to 7 members in order to better serve our projects and community.

We’ve got lots going on with Opulent Voice, Haifuraiya, AmbaSat Respin, and regulatory work.

Amaranth

Amaranth